Vienna

A reverie

Vienna was freezing. Vienna was perfect. Snow fell delicately each morning on our side of the bridge before seeming to abate before we made it to the other side. This gave the impression that it fell only in our quiet gray residential area, and never in the city center. Old women in fur coats smoked stoically on balconies above the window where we sat on light colored wooden barstools, drinking our Melanges and eating little rolls filled with ham, butter, gherkins, and fresh finely ground horseradish. Every few bites an enzymic puff would release and clear our sinuses.

The wide open streets so often quiet and empty were flanked by building after building of unparalleled grandeur. Long roads beset with generous squares and parks, filled with hundreds of rose bushes tagged by common name and wrapped in muslin at their tops, tucked away for Winter. Hedges, sturdy and dark green are left half-trimmed, as if their tender came on Friday to shape the right hand side, left at dusk, and will return Monday to finish the left. Cartoony. Like a man with half a haircut. Long drives open up into vistas populated only by emptied fountains wherein silent white statues in various poses of frozen action keep watch until Summer comes again. Then the mouth of a palace is suddenly visible, backlit and pristine white, its brilliant verdigris roof dazzling bright against more and more grey sky.

The cold quietness of January combined with such a quantity of splendor (truly palace after palace) lends a ghosty air. This combined with our jet lag (9 hours from California) creates a feeling misty and out-of-time. Our eyes sting, surfacing to staticky wakefulness at 4:30am each day. Though now I typically sleep long and well, my teens and early twenties were characterized by a hyper-consciousness, and this early morning alertness makes me feel somehow in touch with a former self. Dani and I lay facing each other, talking in the dark. We lay waiting for the sun to rise, waiting for the cafes to open.

On our first morning we discover the ham & horseradish to which we will become devoted over the next few days and forevermore. The horseradish, different than any I have ever had, is not combined with anything creamy. It is more finely grated, and keeps its form. Looking more like thinly prepared translucent cabbage than the jarred prepared stuff I have more experience with. It is supple, as if softened in a most subtle marination of vinegar, though it does not taste pickled. We go to Joseph Brot, a chain bio-bakery possessing all the markers of modernity we have come to be suspicious of. Light wood, bright but un-sturdy, a millennial Scandinavian temperament. We enter feeling slightly disheartened but desperate for coffee. Everything looks too perfect. It reminds me of the way I felt the first time I entered a Jolene. As if my soul had been poured out of yet another pristine Japanese-inspired stoneware mug.

I remind myself that Jolene’s actual products (good) made the whole thing grow on me a bit more and perhaps this place can too. Our hankering for caffeine and the bitter cold outdoors keeps us put. And thank god because this little sandwich at Joseph Brot will be the amulet that lays ahead each day, at 4:30 in the morning, while we wait for daylight to appear. Joseph Brot is good, everything we tried was excellently executed, but the sandwich, on a little bread roll, soft but in possession of thin enamel crust that just crackles beneath your teeth, is perfect. At first you suspect it is mustard that hits the back of your nose, but actually, it is the aforementioned daintily-prepared horseradish, pressed like jacquard into a swipe of cold sweet butter. Sliced gherkins, just enough, and blush colored ham, thinly carved but not stingily layered, finish it off.

We had a second coffee and grinned at each other over our discovery. A perfect little sandwich is always life-affirming. Afterwards at the Freud museum I am first struck by the austerity of bourgeois 30’s glamour. How I love well made plainness. The brown leather trunks with their shadowy one-hue darker than the leather monograms. A simple white calling card with black cursive name & address. Charcoal grey woolen cap. Tortoiseshell glasses in plain black cases. Nameplates on black granite. An ivory tipped cane. A white door which swings on hinges both directions (what were the intended psychological implications of that? Obvious but I love it.) with a single window in the middle shaped into a mix of angular and fluted edge oval. The collection of antiquities along the shelves of books, their sandstone Egyptian smoothness staring out from brown and burgundy hardback rows.

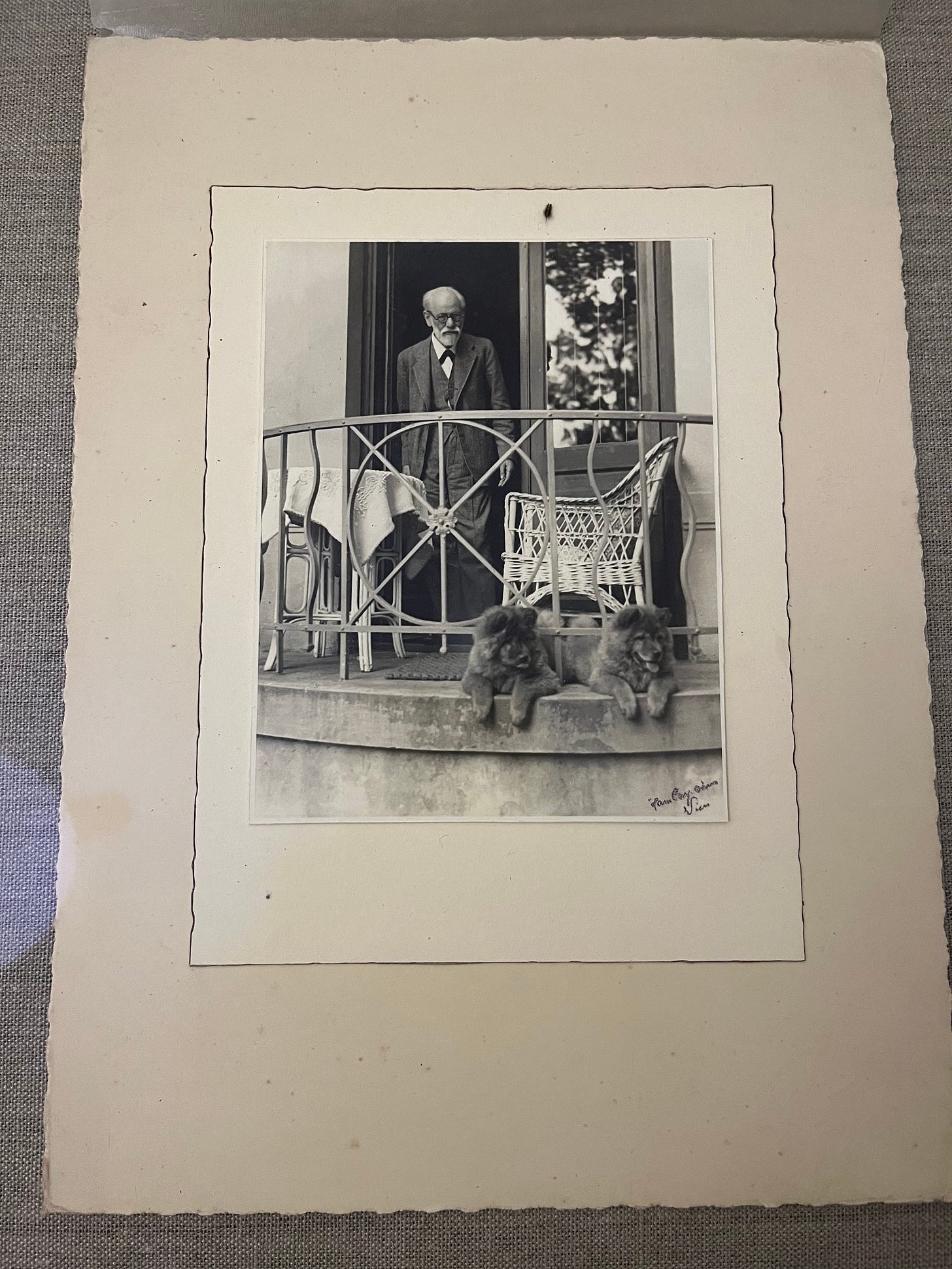

There is a silver, cream, and ebony clarity to every room. Calling out from toiletry bottles, postcards, and decks of cards. The black and white photographs and home movies and info plaques. A stern man on a balcony formed by wavy-geometric wrought iron, stands beside a white wicker chair, twin chow chows peek out from below. Their hue we intuit to be caramel. At a birthday party in a silent moving reel we see the man in a similar wicker chair, but on a lawn, being presented with gifts by dark-haired & dark-eyed family members dressed in fine picnic attire. They are not exactly in a line but give the impression of nearly-institutional choreography. The voice over narration tells us of a jewel, a ring, which was given on that day and later stolen in a robbery.

More than anything I am struck by the interest I feel in the specificities of a given family life. The smaller artifacts and lesser-known stories exist in gorgeous high-contrast black & white. The font of everything thrills me. A wall reads—The only surviving original furnishing: Freud arranged for the wood paneling with wall hooks and raffia infill. And then in smaller font—After being greeted at the door by the maid, Sigmund Freud’s patients hung their coats here, beginning in 1923, Anna Freud's patients did as well. I am seized suddenly with the most desperate distracting longing for wooden paneled wall hooks with raffia infill. How sweet, I think, it is for people to hang up their coats.

I search for things to like in the info plaques. I muse that this urge I always have to search for things I like in any context, might make me a bit stupid sometimes. One plaque talks about his fervor for antiques, another his love of travel and wine, and another in defense of his open-attitude towards sexual orientation reads: A case of Lesbian Love. I chuckle. What am I doing? Tallying up common interests? Indeed. I already know a lot of sour stories about his personality. I am looking for something else.

I did not know that he fled in 1938 to London, and died in 1939. Not long at all. I did not know his sisters, all four slightly younger than he, were left behind and died. 3 in gas chambers and 1, the youngest, in the Theresienstadt fortress ghetto. She was 81. I feel strangely chilled by the idea that you could make it all the way to 81 and have that happen. Disaster, past and present, suddenly confronts me narratively. A play unfolds in my mind of all the ages bad things can happen. There are 81 year olds right now whose lives are being blown up. For some reason, preoccupied as we are by youth (and in some ways rightfully so), this thought feels painful and scary in a newer way. I return my eyes to the book covers.

At another far grander museum, housed in a the baroque Belvedere Palace, I am most interested in the windows. Framed in wood with rounded edges, square tops, and a bisecting line, I am enchanted and find myself daydreaming about having one just the same over my kitchen sink. I actually came here because I am very fond of Klimt and Schiele but quickly begin to experience the crankyness I often feel in museums. Painting after painting, there is only so much I can bear. There is not enough context, not enough living. I don’t get to interact enough. I get scolded for leaning slightly against an enormous marble pillar in the lobby. I feel a flash of rage. What is a giant marble structure in a lobby for if you cannot touch it gently? If it cannot support you? While I know this is irrational my rage is hot and true.

And then, The Kiss. Like visiting the Mona Lisa, onlookers hoard. A print of this once hung above my parents bed. My parents are divorced. There is no causal relationship but the fact remains. I am both touched and annoyed by the real thing. I feel tenderness for a moment and then grumpy. Flattened as it is by my childhood, the inherent basic-ness of knowing something has existed in the mind of the public so broadly and for so long. Been reduced to the printing of a million paper copies at least, that hung unframed above unframed marital mattresses in 1999. Then the gift shop depresses and annoys me further. The Kiss has been badly printed on the shittiest silk robe I have ever seen that looks like every other modern silk robe sold today. For €120 you can be swathed in a runny-watercoloresque iteration of Klimt’s embracing pair, cookie-cutter shape to the robe itself, with no detailing at all in its cheap horrid silk. The magnets, oven gloves, notebooks, fans, and socks in their glaringly wrong palated copies of more and more and more of The Kiss correlate in each glance to my mounting disgust.

When we walk out the giant heavy doors I am glad. The barren Winter gardens soothe me again in their cold air and muted black-green and sand. We head to a cafe Lydie told me about, which like many places here is delightfully open all day long and late into the night. The entrance, pale sea-foam, with a charming old world black sign with gold lettering, reads Kleines Cafe and then in white chalk ugly handwriting on either side reads Cash Only and what appears to be some daily specials. It is a picture which would have tickled me deliriously on Tumbler in 2011 and tickles me still. This doorway seems to foreshadow the entire atmosphere, which strikes me as nostalgic, something I would have cherished so deeply at 17.

The staff, politely disinterested in anyone but each other, are doing a change over and the ones arriving are so clearly the kind that always work the later shift. They wear black jeans, black sweatshirts, and expressions of sexy-nonplus while slightly too aggressive music begins playing in the background. Beautiful teenagers linger luxuriously over glasses of €3.50 red, their feet twitching to play footsy, eyes trained with hard won and deliberate focus at the paperbacks that divide them. Glorious! I want to laugh and kiss everyone. Everyone reading probably The Stranger and eating another local regularity we have discovered—Chive Toast. Quite literally a thick slice of tin loaf with a thick spread of cold butter and a pile of chopped raw chives.

From above the bar stares down a large black and white portrait of some handsome poet-revolutionary. Most likely. I do not know who he is actually and I want to but I’m too shy to try to ask in my poor stilted German when the bartenders are so kindly but thoroughly disinterested in my existence. Maybe they won’t know or care, maybe it is nobody anyone knows of. Still, in the weeks to come I will continue to wonder before finally working up the nerve to look up their phone number online to call and ask. Doing so only to discover they do not have a phone. For the time being I merely stand at a table drinking wheat beer and stare up into his dark eyes, his straight nose, and formidable cheekbones. His hair swooping left with a side parting, extra-long white lapels flanking a thick tie, cigarette tip visible in the kind of mouth that defies undignified death.

All this gets me thinking about Stefan Zweig. About Julie Delpy’s little white t-shirt under her ankle length 90’s jersey slip dress. About smoking cigarettes when you’re 15. My mind swirls with the knowledge that once, in Vienna, the average citizen looked to their newspaper to read about local theater long before his eyes scanned anything related to foreign affairs. A society at the heart of European arts and culture, possessing a metropolitan center uniquely unsegregated from the Danube, the gardens, the vineyards, the foothills of the Alps. I think of the hyper-eroticism of victorian morality, a predicament curiously no longer propelled forward entirely by religion, but by a new code, just as staunch, decorum. The decimation of a war, or two, which seemed so impossible in a time and place of totally flourishing optimism.

As Zweig says in The World of Yesterday: “But for all the solidity and sobriety of people’s concept of life at the time, there was a dangerous and overweening pride in this touching belief that they could fence in existence, leaving no gaps at all. In its liberal idealism, the nineteenth century was honestly convinced that it was on the direct and infallible road to the best of all possible worlds”. Touching belief, I think to myself, knowing exactly what he means. Best of all possible worlds.

This dream is still felt in Vienna and it does manage, whether illusorily or not, to bridge gaps. For the Habsburg Empire I go to Lobmeyr. To feel like nothing really bad could ever happen to me I go to Lobmeyr. Surrounded by all this breakable glitter I am safe. Though for now I cannot afford the gorgeous fan crafted from softest navy blue leather, each section like some perfectly formed eternal feather. Nor the perfumes whose notes trace the achievements of the Austro-Hungarian empire in woody-lactic thrall. Nor the lacquered trays, in sunflower yellow, trimmed in white, and gleaming pristinely on the upper floor where a woman dressed in sumptuous black wool inquires casually about the price of the massive chandelier above our heads. I get to exist on this earth, in this room, with these objects. My will to live is reaffirmed by their very fact. There is a Biedermeier elegance and democracy to merely walking around these rooms.

Vienna is a place I would have loved at 17, love still, will love at any age. As I go from place to place my consciousness is flooded by a cultural thread that spans from Rudolf I in 1273, to the foppish coif of Ethan Hawke, to me, on this Monday right now. All the aesthetic symbolism that spectrum contains washes over me in waves of sensory information and pleasure. Its zenith occurs at Zum Schwarzen Kameel, an institution I would liken to Sweetings in London, or Russ & Daughters in New York—but even older. Opened in the same location it remains today in 1618 by Johan Baptist Cameel as a spice shop, it evolved as a haven for many an imported good, including fine wines. Two centuries later Joseph Stiebitz acquired it, keeping the wine and spices and expanding into an esteemed delicatessen. He eventually became a purveyor to the court in 1825. In 1901, a new building was erected, and the classically art nouveau interior it still possesses was installed.

In its current model it is split basically into three sections with a large red overhang covering an additional swath of alfresco cafe tables at its front. On the right hand side is a delicatessen where bottles of wine are lined up in pristine formation on shelves above offerings such as whole sides of smoked salmon, cured meats freshly sliced, and housemade chocolates boxed into perfect rounds illustrated with a black camel resplendent in gold tasseled red cloth and feather headdress. The center of the building contains a more formal restaurant, with white table cloths and coat stands. To the left is the bar, bridged by a room possessed of an eye catching assortment of jewel-like pastries and open faced sandwiches, both of which can be boxed up to go, or handed to you on a small white plate, along with your ticket, to take to the bar and present to your bartender once ready to leave.

It is an atmosphere of sophisticated jollity. The waiters, none in quite the same ensemble, are made similar only because they wear either white suit jackets or navy blue shirts (not the same shirts, just all navy) with neckerchiefs (not the same neckerchiefs mind you, silk ones of different patterns, as if brought from home). In their little recipe book and online they stress the tradition of egalitarian mingling this space has always encouraged. Wealthy merchants rubbed elbows with carriage drivers rubbed elbows with Beethoven if you catch the drift.

Best of all possible worlds. I think to myself again and of Zweig’s other line “Our fathers were doggedly convinced of the infallibly binding power of tolerance and conciliation”. This dream of course, is blown apart, and never stopped being blown apart, though every couple of decades we fiddle with it again. Zweig, conceding its delusion, still calls it wonderful and noble. I enjoy its suspension of disbelief, but I wouldn’t call it noble.

I might say that I enjoy the obviousness of its dimensions. Like, if let lose in a city I am often (though briefly) troubled by a feeling of my own class-traitor impulses. In this place that sense of tension is assuaged slightly if only because it is overshadowed by Vienna’s own obvious and similar consciousness. Entirely un-diverse, and so full of the very very grand, it is waiting, eagerly, to demonstrate its tolerance for everything it is not.

On the other hand, we cannot stop dreaming of a democratisation of beauty and pleasure. So perhaps Stefan was right.

Should you tire of schnitzel and other Viennese traditions it is a good idea to go to Cà Phê Lalot, a small recently-opened daytime cafe run by Viola Waldeck and Lukas Stein. Online his influences are attributed to a background in “Wirsthaus” bistro cuisine and his Vietnamese heritage. Hers to illustrious Danish training and an appreciation of “Nordic Minimalism”. In any case they are nice to chat to and serve breakfast and lunch. The space is comely in a familiar millennial sense. Atop a light wood bar sits a gleaming La Marzocco where my eyes settle on a pleasing stack of Nankin blue china cups destined for cortados. Beside, an immaculate glass pastry case houses a row of green centered bronzed pandan canelé. The seats are pleasingly industrial steel stools. The tables real marble, small, and round.

Though I have seen it all before I don’t mind. The whole thing is made real by Viola and Lukas actually being there. If the things a generation of a certain kind of people like have been distilled in this room, they have been distilled well. It is suddenly comforting rather than soulless, because it has been created rather than manufactured. In the morning there is a small selection, roughly 5 items, things like congee, or an omelet with asian mustard greens and lemongrass chili oil. For lunch just one dish is served (I am a fan of this). On the day we go it is a wonderful soupy curried eggplant dish with a warm puck of rice and thin batons of tart granny smith that delight me. We drink Gut Oggau’s Winifred from a yellow ice bucket at noon. It’s rosy acidity socializing perfectly with our lunch. This is the first wine we have drunk since we arrived, and we ask Viola and Lukas if there are any other spots they might recommend for good Austrian natural wine. They kindly make us a little list.

I will begin at the second recommendation we visited because I liked the first much better. Rundbar is perfectly fine but it doesn’t get my blood going. The countertops are terrazzo, the plates pale and rimmed. Wine glasses are either Zalto or a tasting glass emblazoned with “No Borders” but the waitstaff are both on laptops for the whole first hour we are there. Too busy being busy, modern, and good to be charming at all. It is an atmosphere of dull, specific, and contemporary self-awareness but I will concede that their Wine List is good.

Espresso, on the other hand seems to exist out of time. Not only am I tickled by their deeply un-googleable name (it will eventually surface as Cafe Natural Wine Bar Espresso) but by the young man who so excitedly engages us when he realizes we care about wine. It is casual, something for everyone. Kids on laptops sit on one portion of the room on sofas, people eat meals though it is the odd hour of 3:00pm, the bar is busy with people laughing and drinking. Nobody working seems annoyed by this mishmash, and I find myself lecturing myself internally about my own rigidity. If a tendency towards hip sterility is my main critique of certain parts of this town, Espresso is the opposite of that. The ceiling is tall, the color of sand, and still adorned with remnants of the original floral frescoes from the Jewish bakery it was pre-1938. Relatives of that family, the waiter informs me, have actually come to visit. Everything else is youth hostel meets 1960’s kitsch.

The atmosphere is lively, it is peopled and pleasantly disorganized. Their house pet nat, made for them by a winemaker who is also a friend, is incredibly delicious. As is the Silvaner I drink afterwards. I am having such a nice time, and taking this waiters’ very good recommendations, and thus forget to take note of the specifics of anything we drink. I do recall in his excited chatter, him telling me about Roter Veltliner, which I had never heard of (what we might consider a grey-skinned varietal, like Pinot Gris, ranging in color from greenish-yellow to a blushy pink). Once again I am struck by a quality of life that seems bygone (or perhaps just fantastical) where businesses are open all day, seem to have enough staff, seem not to have to make themselves lean and hyper focused to be viable.

On our very last morning I lay awake at twilight when suddenly the sounds of Frank Sinatra singing Strangers in Night begins to echo down from the apartment above. This apartment’s inhabitant also begins to sing along loudly and whistle. Dani and I begin to laugh, and Frank croons and croons as the sun pierces the horizon of our blinds in camp cinematic unison.

What else? We saw the Lipizzaner horses practicing at The Spanish Riding school. Watched them piaffe, or trot in slow motion, as if their hooves were suspended over a carousel music box. The long brown tail coats worn by the riders have a special compartment in the back just for sugar cubes, to give the horses. I like that. We strolled through artful stacks of candied violets at Demel with all its shining wood, and guilt, and tiny cakes, and cream. A sweetness in the air permeated everything, leaving sweaters smelling floral and crystalized.

In the same square we go to Loden-Plankl to try on gorgeous felted sheep’s wool gilettes and green capes trimmed in fox fur. I meander through racks of dirndls and velvet busts pinned all over in Edelweiss. There is even a wool umbrella (the felting process of making loden wool renders it waterproof), which thrills me most of all.

In the evening we have booked an Opera, at a small house, as in January most of the larger houses close up for a break. It is the first evening we have attempted staying out past 7pm and by the time we take our seats we are already exhausted. We struggle to keep our eyes open, and the show is bad. More a musical than an opera, with a storyline altered to be more “modern”. We both fall asleep and jolt awake multiple times and when the intermission comes we decide to leave. There is a naughty childlike thrill to this desertion. For the ongoing revelation that we are grown up and have bought the tickets ourselves, and thus we can chose to abandon it. We head to the sausage cart we found on our first night, having arrived too late for most things to be open. A small stand on a corner brightly lit by street carts. We order Käsekrainer (cheese filled sausage) and Bratwurst, with sides of pungent mustard, and little plates of dark rye bread.

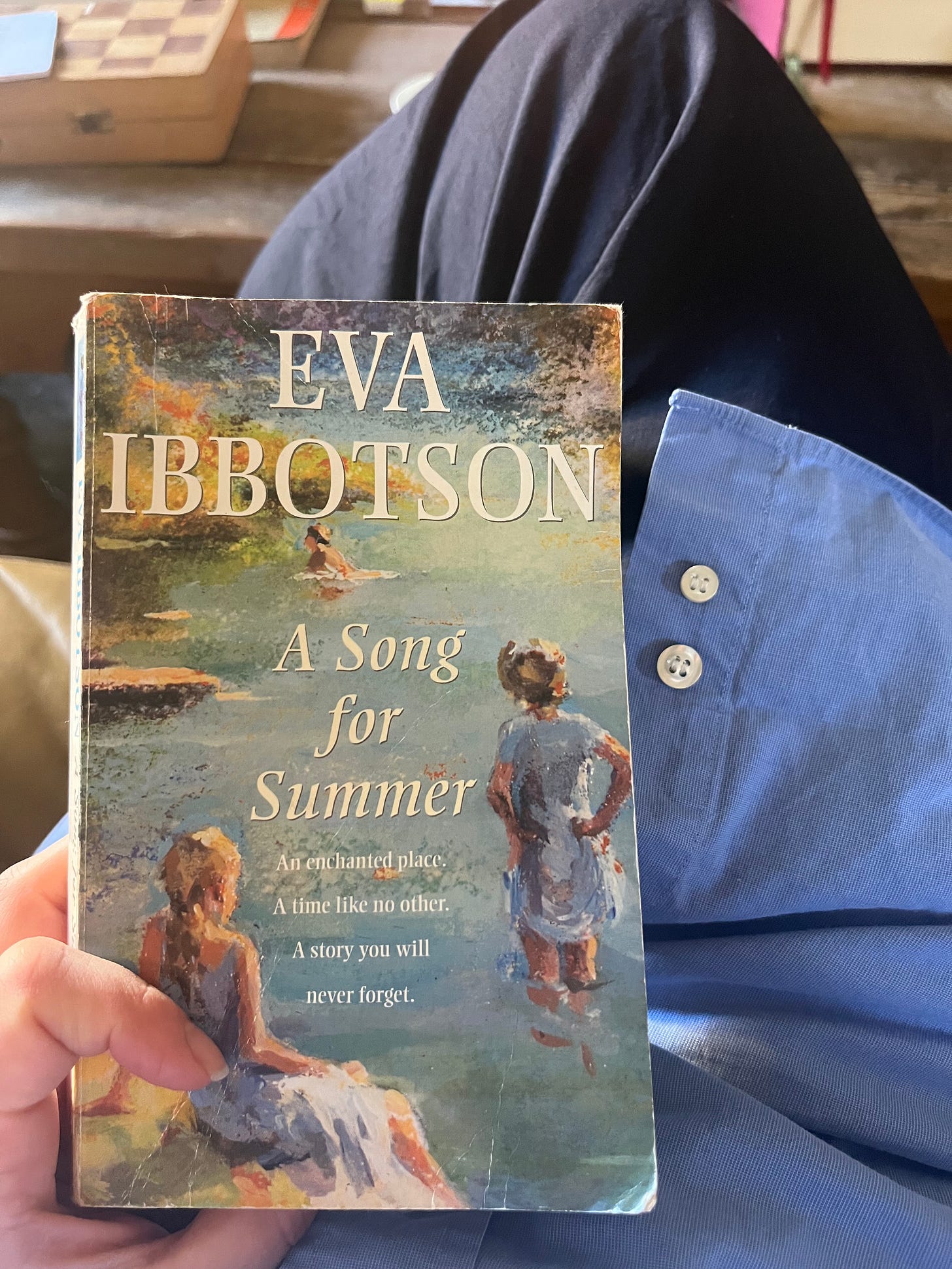

I left Vienna knowing I’d be back. All its details have continued to echo in me, bouncing around my mind in a thematic reverie spanning and connecting centuries. I have been helped along by a friend recommending I read some Eva Ibbotson at just the perfect moment. So I will now recommend it to you!

They are easy books, destined for balmy reading and a favorite regular at the restaurant has informed me not wholly historically accurate. Luckily I am not reading them for fact, I am reading them for atmosphere. For Austrian reverie. For the belief that in the face of destruction and fascism (topical), a love of art and music, a celebration and protection of differences between people, and a commitment to nature and to gentle husbandry of the land, shall save us all.

Set usually around the 1st or 2nd world wars, there is always a love story, often some dramatic change in circumstances, some almost fatal misunderstanding, and a great capacity for understanding the emotional range of the human psyche. A sense of humor and will which beams out from tragedy and declares “she wants a better world for the poor and oppressed — and she wants to look pretty while she’s getting it — and don’t we all” (Madensky Square, 11).

My favorite so far is A Song for Summer. A book that makes me want to till the garden and scrub the kitchen floor merrily. For while I know that polished silver and a lovingly tended vegetable patch will not solve all the world ills, it is not, I maintain, a bad angle from which to toil. If Eva reminds us of anything it is that our greater despair cannot cause us to be neglectful of what is right in front of us.

Sending love to you all xxx